Major league players have moonlighted in some unusual ways over the years

I recently read about how Padres reliever Mark Melancon moonlights with his own turf installation company. Nowadays, with a minimum major league salary approaching $700,000 a season, there is little need for big-league players to moonlight away from the field. Before the dawn of free agency in 1976, it was pretty routine – and necessary – for most major leaguers to find winter work. For example, the minimum major league salary in 1975, the year before free agency, was $6,000, while the median family income in the United States was $13,720. Data from 2020 shows that the average American family earned just shy of $88,000, or about eight times less than the minimum scale in MLB.

Many players years ago held down typical jobs, such as selling cars or insurance. Here is a shortlist of odd jobs of major league ballplayers that I’ve recounted during broadcasts over the years.

A Grave Situation

When I was young, I remember hearing about how Richie Hebner, who enjoyed his most significant years with the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1970s, worked as a gravedigger in the offseason. It turns out it was a family business that his grandfather started. Hebner spent 35 years digging graves the old-fashioned way – with a pick and shovel. The former third baseman gave new meaning to “digging one out of the dirt.” He was honored many years later with his unique bobblehead (see above).

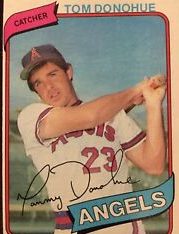

The Angels had a catcher, Tom Donohue, who had a short-lived major league career with the club in the late ’70s. While playing, Donohue was also studying to become a mortician and would often read his mortician books during team flights. He certainly didn’t lack a macabre sense of humor. According to th e story, during a particularly turbulent flight, the backstop regaled his unnerved teammates by reading aloud excerpts from one of his mortician books about preparing the remains of charred crash victims properly. As if that weren’t enough, he reached into his bag and passed out toe tags to his fellow players.

e story, during a particularly turbulent flight, the backstop regaled his unnerved teammates by reading aloud excerpts from one of his mortician books about preparing the remains of charred crash victims properly. As if that weren’t enough, he reached into his bag and passed out toe tags to his fellow players.

While we’re on the subject, Hall-of-Famer Waite Hoyt, who led the American League with 22 wins for the 1927 Yankees, considered a career as a mortician at one point. His father-in-law owned a funeral home. On his way to Yankee Stadium one day, Hoyt stopped by a hospital to pick up a corpse, loaded it into his trunk, and drove to the ballpark, where he tossed a shutout. Following the game, Hoyt jumped in his car and delivered the corpse to his father-in-law’s funeral home. Evidently, he decided that tossing shutouts was more gratifying than tossing dead bodies into his trunk.

There’s No Business Like Show Business

This following snippet isn’t about an odd job of a major league ballplayer but rather that of a legendary manager.

John McGraw was known as the fiery leader of the New York Giants, with the disposition of a wild boar. There was a reason he earned the moniker “Little Napoleon.” McGraw skippered the Giants with an iron hand from 1902 – to 1932, winning more games than any other manager in National League history.

You may not know that the temperamental manager once tried his hand at vaudeville. In 1912, he went on a 15-week tour during the off-season, performing six days a week in numerous cities, including New York.

While he was no Laurence Olivier, reports are that he was no slouch. However, he wasn’t a huge proponent of rehearsing. As the story goes, the show’s writers would put the skipper in a taxicab and instruct the driver to cruise around Central Park until McGraw memorized his lines.

May I Have This Dance?

Don Rudolph had a relatively obscure six-year major league career, bouncing among four organizations and finishing with an 18-32 record. When discussing the odd jobs of major league ballplayers, Rudolph must be near the top of the list. In the mid-1950s, he and a few teammates decided to pass some time by taking in a burlesque show featuring a popular local stripper named Patricia Brownell, known on stage as Patti Waggin. Rudolph immediately became obsessed with the gal. After turning down numerous advances from Rudolph, Brownell eventually acquiesced and married him.

Rudolph’s new offseason gig? He worked as his wife’s manager and publicist. During her shows, he was responsible for, among other things, catching her clothes as she flung them offstage during performances.

Today, side jobs are a ritual for minor league ballplayers. Their salaries are a pittance compared to their major league brethren. Many minor leaguers utilize their talent to provide paid pitching or hitting lessons during the offseason to make ends meet. Endorsement deals can sometimes exceed a lucrative major league salary if you’re good enough to reach the major leagues and become a star.

Play It By Ear

The great Christy Mathewson was one of the first major league players to take advantage of his fame. Mathewson spent most of his 17-year career pitching for the New York Giants. His legendary status led to numerous endorsement deals, including shirts, collars, undergarments, and athletic equipment.

Unlike some major league ballplayers, Phil Linz didn’t have an odd job; he had a fortunate incident that led to a lucrative payout. Linz was a backup infielder over his seven-year career. He broke in with the Yankees in 1962. By 1964, Yogi Berra had assumed the role of manager for the Pinstripes.

Late that season, the Yankees team bus was headed to the airport following a four-game sweep by the White Sox. Linz had picked up a harmonica at a local shop during that trip. During the ride to the airport, he sat at the back of the bus while practicing Mary Had a Little Lamb.

Sitting at the front of the bus, Berra was in no mood for the cacophony behind him. The Yankees manager shouted for the music to stop.

Linz evidently didn’t hear his skipper and turned to ask Micky Mantle what Berra had said. The veteran Mantle, sensing chum in the water, told Linz that Berra said, “Play it louder.”

Linz continued to blow into his harmonica when Berra angrily rushed to the back of the bus. Yogi knocked the instrument from Linz’s hands and announced that he was fining the infielder $250.

After national story reports began to surface, the Hohner harmonica company offered Linz a $10,000 endorsement deal. For comparison’s sake, that’s equivalent to roughly $85,000 today.

Following his retirement, Linz became a successful business owner, running a popular Manhattan restaurant and club.

So, there you go – a shortlist of some odd jobs for major league ballplayers – and a couple of endorsement deals. By no means a comprehensive report, but a few of my favorites from over the years. If you enjoyed the article, please feel free to click on the comment link below. From there, you can like, share, or comment on the post. If you have any favorite odd jobs of major league ballplayers that you’d like to share, I’d love to hear from you. Thanks for reading!